|

|

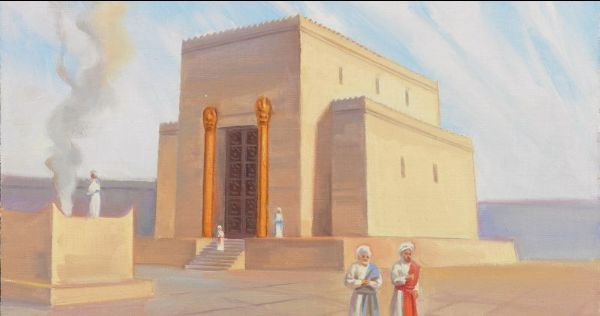

2 Kings 17–25 – “He Trusted in the Lord God of Israel”

“Hezekiah’s Tunnel Vision,” Charles A. Muldowney, Ensign September 2002 “Hezekiah’s life is a study in courage and faithfulness before the Lord in the face of extreme opposition. However, when his greatest test in life came, he faltered, leaving a tarnished legacy and laying the foundation for the eventual scattering and destruction of his people.” “Five Empires of the Ancient Near East: A Historical Backdrop of 1 Kings to Matthew,” John A. Tvedtnes, Ensign, April 1982 The book of 2 Kings covers the kingdom of Judah’s interaction with neighboring kingdoms. This short article provides maps and an overview of the changing empires of the region. “Is the Bible Reliable? A Case Study: Were King Josiah’s Reforms a Restoration from Apostasy or a Suppression of Plain and Precious Truths? (And What about Margaret Barker?” Eric A. Eliason, BYU Studies Quarterly 60, no. 3 The chapters 2 Kings 22 and 23 help scholars understand how the Old Testament took its shape and its main themes. The story tells that the scroll commanded eliminating all potential rival worship sites and concentrating attention on Jerusalem. Some scholars see in this a loss of older doctrines, such as God’s wife and son and a plurality of Gods. Margaret Barker’s books in particular have been enthusiastically studied by some Latter-day Saints. Was Josiah a righteous reformer, or an agenda-driven power consolidator/narrative reshaper worried about the Assyrians, or a suppressor of a religion that was more beautiful and richly populated with divine beings? Read about the dispute and how we might consider Josiah’s actions. “Joseph Smith and Preexilic Israelite Religion,” Margaret Barker, BYU Studies 44, no. 4 Josiah’s reforms can be seen as a purge. Older teachings such as those from the time of Solomon’s temple have been lost and are now to be found only in texts outside the Bible. Certain passages in the Book of Mormon resonate with the lost themes. “Amos through Malachi: Major Teachings of the Twelve Prophets,” Blair G. Van Dyke and D. Kelly Ogden, Religious Educator 4, no. 3 “King Hezekiah of Judah (715–687 BC) rebelled against the overwhelming power of Sennacherib, king of Assyria, during the ministries of Isaiah and Micah. The result was that the forces of Sennacherib pummeled every major stronghold of Judah except one. With those victories behind him, Sennacherib turned his armies toward Jerusalem. With destruction seemingly imminent, Isaiah prophesied that Sennacherib would not even shoot an arrow in Jerusalem, let alone conquer her (see 2 Kings 19:6–7, 32–33).” “The Restoration as Covenant Renewal,” David Rolph Seely, Sperry Symposium Classics: The Old Testament, (2005): 311–336 “Another instructive example of a covenant–renewal ceremony can be found in the account of the reforms of Josiah in 622 B.C. (see 2 Kings 22–23). During the course of renovation of the temple, Hilkiah, the high priest, found “the book of the law” in the house of the Lord (2 Kings 22:8), which had apparently been lost or forgotten. King Josiah, upon hearing the contents of the book, was distressed and sent for a representative of the Lord–the prophetess Huldah–to ascertain the validity of the covenant contained in the law. In a sense, Huldah provides the Preamble to the covenant ceremony when she declared that in fact the Lord was the author of the Stipulations contained therein (see 2 Kings 22:16). Furthermore, Huldah prophesied the destruction of Israel, declaring that the Blessings and Curses associated with the stipulations “even all the words of the book which the king of Judah hath read” would stand as a Witness against Israel’s disobedience and would all be fulfilled (2 Kings 22:16–17). Josiah immediately gathered the people “both small and great” to Jerusalem, where he Publicly Read “the words of the book of the covenant” (2 Kings 23:1–2) to the people. Then the king led the people in covenanting before the Lord to “perform the words of the covenant that were written in the book” (2 Kings 23:3). Israel’s apostasy and the need for covenant renewal are graphically illustrated in the almost incredible description of the abominable objects that were brought out of the temple of the Lord and the idolatrous and immoral practices that were once again outlawed (see 2 Kings 23:4–20).” “The Great Jerusalem Temple Prophecy: Latter–day Context and Likening unto Us,” Jeffrey R. Chadwick, Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament “The great Jerusalem temple prophecy, found in Isaiah 2:1–3, is one of the most remarkable passages in the Hebrew Bible, or indeed, in all of ancient scripture. At some point in early Jewish history, perhaps around 620 BC, during the reign of King Josiah, the admonitions that now constitute Isaiah 1 were placed in their current position as “the Lord’s preface” to the entire book of Isaiah.” “The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context,” Kevin L. Tolley, Religious Educator 20, no. 3 Zedekiah reigned in a time of spiritual, economic, and political turmoil. Lehi was one of many prophets during this time, including Jeremiah, Obadiah, Nahum, and Habakkuk. Zedekiah’s councils could not accept Jeremiah’s prophecies and worked to have him imprisoned. The context of the situation in Jerusalem gives insight into the early events of the Book of Mormon. |